By altering atoms, Mike Carlson has made more things disappear in water than the mob. Now he’s coming for you.

A DECADE AGO, Mike Carlson invented NanoNets, molecular agents used to radically improve wastewater chemistry. He took them to Texas to work on frack wastewater and, a decade later, owns 75% of the market.

Now Carlson is coming for Food & Beverage wastewater. In the last year, he’s used NanoNets to help two of the world’s biggest F&B producers shave millions off their OPEX, CAPEX, and emissions.

We’re colleagues of Carlson but wanted to interview him for this piece. We reached him while he was on location in California. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You’ve been quoted as saying “there’s too much waste in wastewater.” What did you mean by that?

MC: The job of wastewater chemistry is to remove particles in water so you can return the water back into the system, and the particles to landfill [in the form of sludge].

The problem is that the old chemistry doesn’t work. You spend 100% on a chemical that only does 20% of its job.

Q: Why would a producer buy chemicals that aren’t doing their job?

MC: Because wastewater treatment hasn’t changed much since it was introduced in the 1950s. Water was abundant and there weren’t many regulations. Bad chemistry didn’t matter.

Q: And now it’s reversed.

MC: Right. Water is now scarce and regulations are abundant. Wastewater is becoming costly—and because of that, strategic.

Q: How are you seeing that play out in Food & Bev?

ML: A few ways. One is reducing the cost of chemicals that producers buy. NanoNets can cut polymer by 80%, and get the overall cost-to-treat down by up to 50%.

Another area is reducing fines. Operators are charged on the PPM they return to municipal, so clarifying that water—getting out as much of the suspended solids—reduces fines.

Q: How much fines are we talking?

MC: It varies from state to state, but some producers pay millions because their water isn’t clear enough.

Finally, there’s sludge. Weak polymers leave too much water in the sludge, which causes problems with dewatering equipment. And some sites have trucks hauling away heavy, soggy mud. You pay by the weight. It’s wasted money.

Q: This sounds like a bit of a slam dunk for the CarboNet sales team...

MC: Yes and no. Yes, because we have the data and can show the savings. But some producers don’t like new things—and rightly so. They’ve been burned in the past by products that didn’t deliver and screwed up their water.

Q: How do you get around that?

MC: Sometimes we don’t. Sometimes an operator doesn’t want to take the risk. But more and more are coming around. We do bench trials, then field trials, then scaled trials…the process is managed. You’re de-risking as you go.

Q: Is there an “ah-ha” moment?

MC: Yes, but it’s different for everyone. A manager at a smaller plant might have an issue with rising chemical costs, and we cut that down. A big manufacturer might care about emissions for plants in one state, but sludge costs in another.

Q: Before you go, what’s SpecialOps?

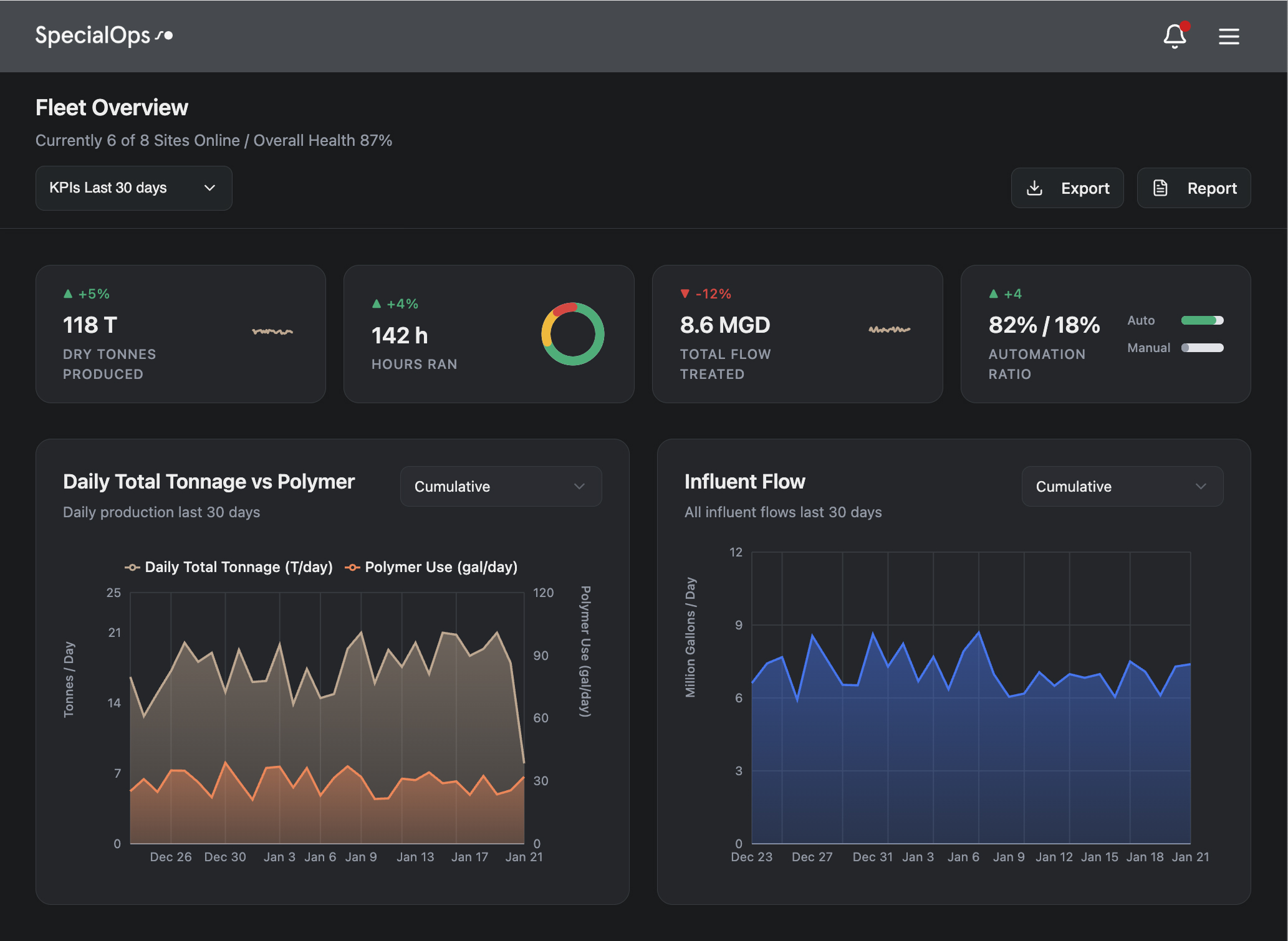

MC: SpecialOps is our automation service. We use telemetry to remotely dose, and provide data in the cloud. So the crew running around the sites can check on their phones while the accountants at HQ can analyze spend.

Q: So, water-as-a-service?

MC: Chemistry-as-a-service, but yeah.

Q: You could have let me had that. No one calls it chemistry-as-a-service.

MC: Sorry. But, to be fair, I’m the boss.

Randy Khalil, Dewatering & Water Treatment SME

Treating F&B Wastewater? Let's Talk.